What have Hamptonites got in common with farmers in Panama?

What have Hamptonites got in common with farmers in Panama?

The bad news: We’re both destroying our land and its biodiversity. Not to mention lacing our precious environment and ourselves with harmful chemicals.

The good news: East Hampton’s celebrated gardener Edwina von Gal is helping both to get out of the dark ages of chemical dependency and show us how to grow our crops and lawns toxin-free. After spending years in Panama helping save the rainforest, she realized only recently that Hamptonites were just as guilty of flinging chemicals around, thus she founded the Perfect Earth Project, a foundation that educates local homeowners on how to cultivate both lovely and healthy lawns.

“The most widespread pollutants in our water supply are the chemicals we put in our yards and gardens,” Diane Lewis, M.D., told an audience in August at Guild Hall. Dr. Lewis was one of six members of a panel discussion led by Ms. Von Gal at the East Hampton cultural institution’s Garden as Art program, which this summer focused on nontoxic gardens, including a tour of several of the South Fork’s most prized examples.

The panel was comprised of several experts including Sean O’Neill, on staff at Perfect Earth, who launched the discussion with his “scare and share” tactic, first scaring listeners with alarming statistics, then sharing the how-tos of chemical-free gardening. “Homeowners use two to three times more pesticides on their lawns than are used in agriculture in this country,” he said. The most common lawn pesticides are carcinogens, neurotoxins, endocrine disrupters, etc. For parents, the news is dire: “Over 50 percent of pesticide exposure occurs during first five years of life . . . and 11 common pesticides are linked to birth defects.” Scary indeed. He posed a poignant question: “Is it worth [such disease] to kill the dandelions?”

Paul Tukey, who was introduced as the “father of the natural landscape movement,” also referenced dandelions, a delicacy his Maine-farming grandmother served up every spring. “How have we gotten from there to here in two generations?” he asked. The founder of SafeLawns is now dedicated to keeping the grounds of the Glenstone Museum in Maryland totally organic. He showed images of the museum’s exquisite rolling lawns where, he said, the occasional weed could be found. “We’re not going for perfection,” he said, adding that they settle for “green and lush.” His solution is to “fix the soil” so that it wants to grow grass, not dandelions.

Stephen Orr, garden editor of Martha Stewart Living, encourages people to go toxin-free with an aesthetic approach. In his book Tomorrow’s Garden, he showed how some pioneering souls around the country were turning areas of their lawns into vegetable patches or replacing grass with more

sustainable native plants or even splendid rows of stones. In his latest book, The New American Herbal, he explains how his own yard, located upstate, is almost entirely made up of herbs – 200 varieties. “Herbs do best when not fertilized,” he maintained. “They take care of themselves.”

Speaker Eric T. Fleisher has the honor of keeping the park at Battery Park City completely organic, the first public park to be managed so. Quite a formidable feat considering that the 34-acre greensward is visited by up to 25 million people a year. He also convinced the powers that be at Harvard to go organic and he continues to sustainably care take Harvard Yard.

Dr. Lewis, who founded The Great Healthy Yard Project, explained how the organization encourages her neighbors in Bedford to pledge to maintain toxin-free yards – a cause that needs a champion in the Hamptons. She left us with her motto, shared by her fellow panelists: “It’s so easy to fix.”

Fortunately there are many local businesses ready to help us do the fixing including Marders, which offers talks on organic gardening, Piazza Horticultural, which focuses on toxin-free landscapes,

Treewise, who call themselves “the organic experts,” and Geoffrey Nimmer Landscapes. All in all, the message is clear: It’s surely not ‘better living through chemistry.’

LOCAL GREEN LANDSCAPES

At Guild Hall’s Garden as Art tour, several nontoxic properties were featured. As Judy and Ennius Bergsma, owners of the enchanting 10-acre Round House estate in East Hampton, showed visitors

their sprawling nontoxic landscape, they stopped near a pair of 80-year-old weeping beech trees to bewail a sad truth: Though two years ago they counted at least 200 monarch butterflies alighting there on their annual migration, this year they only counted five. They blame it on Monsanto’s pesticide blitz of the Midwest through which the Lepidoptera travel on their way here. “The flocks have been decimated,” they opined. A tour through their gardens, an Eden teeming with a bank of

endangered pitch pines, a Japanese-style pond, and fern glen, reveals more bad news: a dearth of once plentiful bats (which eat mosquitoes) and woodcocks (which eat ticks).

The Bergsmas, like all good organic gardeners, believe in letting “the land tell you what it wants to do.” When moss started growing in a shady area they asked themselves, “Why change it?” and now they have a verdant carpet of moss.

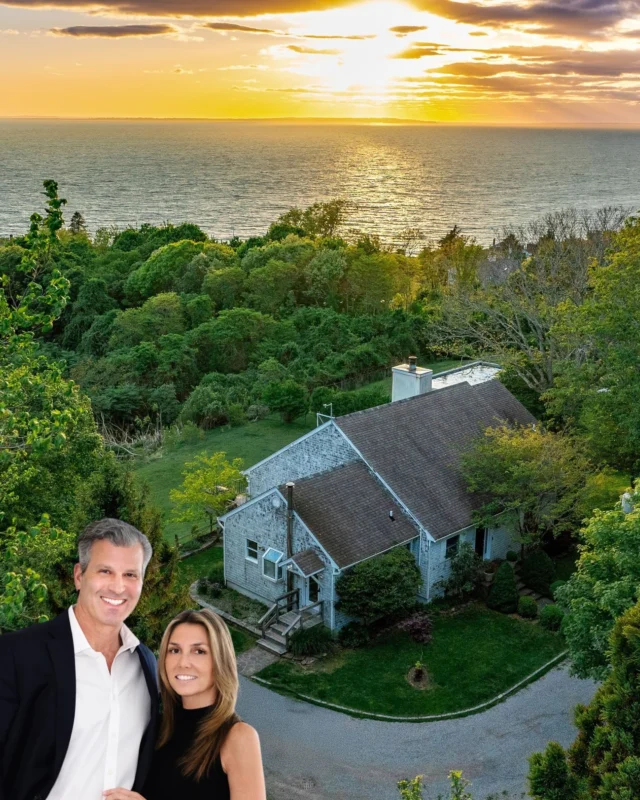

Fred Stelle, a celebrated Modernist architect, and his wife, Bettina, had the same idea at their North Haven bay-front spread. Letting nature take its course, they don’t mow – allowing

indigenous grasses and so-called weeds, such as thistle and milkweed, to grow to majestic heights throughout their pastoral property. A single mown swath provides a walking path. They leave the red clover alone too, letting it provide sustenance for their hives of honeybees. A natural fungicide made of kaolin clay and water, sprayed on their fruit trees, works to keep predators at bay and keep the bees healthy.

Susan Dusenberg, a bayside neighbor, hired landscape architect Jack deLashmet to plant mostly native grasses, which thrive without chemicals, in layers of subtle color, forming a textured botanical tapestry – the ideal nontoxic environment from which to observe the bounteous wildlife including legions of egrets, ospreys, swans, and herons.

Lauren Aitken divides her time between Manhattan and the Hamptons where she gardens, entertains, and sometimes manages to relax.

![When clients embrace bold ideas, the results speak for themselves. In this Sag Harbor home, designer Jessica Gersten played with sculptural form and layered textures to create something truly distinctive. From the forged-iron swing to a striking stairwell pendant that anchors the heart of the space, the finished design balances personality and livability in every room. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/586881005_18549106426030135_1053520189449566580_nfull.webp)

![Across continents and architectural styles, a distinct vision emerges. 🌎 George Lucas’s real estate portfolio brings together expansive ranchland, oceanfront enclaves, heritage estates, and city landmarks, each chosen with a curator’s eye. From Skywalker Ranch’s 4,700 acres to a secluded stretch of the French countryside, his properties honor place, history, and the pursuit of meaningful design. It’s a collection that speaks quietly, yet with remarkable depth. [link in bio]

📸: Araya Diaz/WireImage, Patrick Durand/Getty Images, Mike Kemp/In Pictures via Getty Images, Google Maps, Google Earth](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/582214036_18548535424030135_3221221365131655942_nfull.webp)

![The magic of the movies is having a moment 🎬 From restored architecture to intimate screening rooms and curated cultural programs, today’s theaters are transforming into places where nostalgia meets innovation. Because sometimes, a great night out starts with popcorn and a story worth telling. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/583588404_18548343766030135_6137669070907015384_nfull.webp)