Hope Sandrow’s Art Activism Transforms Lives

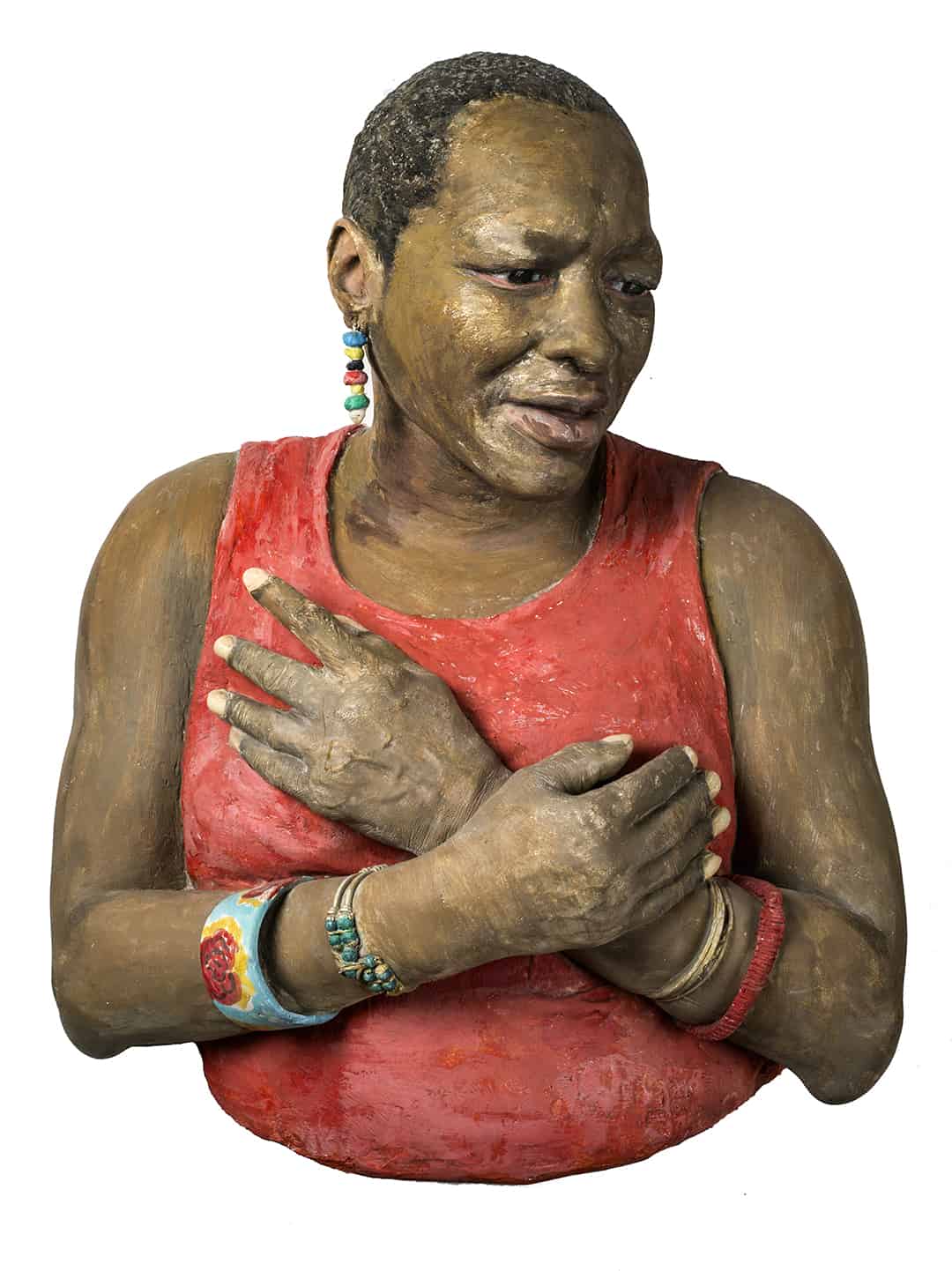

How do you keep your humanity in circumstances that are inhumane? For Hope Sandrow the answer is art, and specifically art as a catalyst for change. “Art is life and life is art,” says Sandrow, “the prism through which to live my life.” Sandrow does not shy away. She does not sugar coat. Where there is darkness, she bravely shines a light, finding not only her own voice but giving expression to others.

Eerily reminiscent of current events, Sandrow’s great grandparents ran for their lives from Ukraine at the turn of the 20th century. This family legacy led to a defining question, “What is the importance of art to people who have lost everything?”

Younger years framed by an era of dissent and the civil rights act of 1964 grew to life-long community engagement for Sandrow. While her works were acquired by the Whitney, MOMA and The Met, she also was keenly aware of discrimination against women artists.

“I made art in the ‘80s that alluded to my viewpoint of looking at art on museum walls – for example paintings celebrating the rape of women – called masterpieces,” says Sandrow who wanted to switch the narrative from being directed by men, “I walked NYC streets and picked up men and asked them to pose for my camera. I flipped the gaze.”

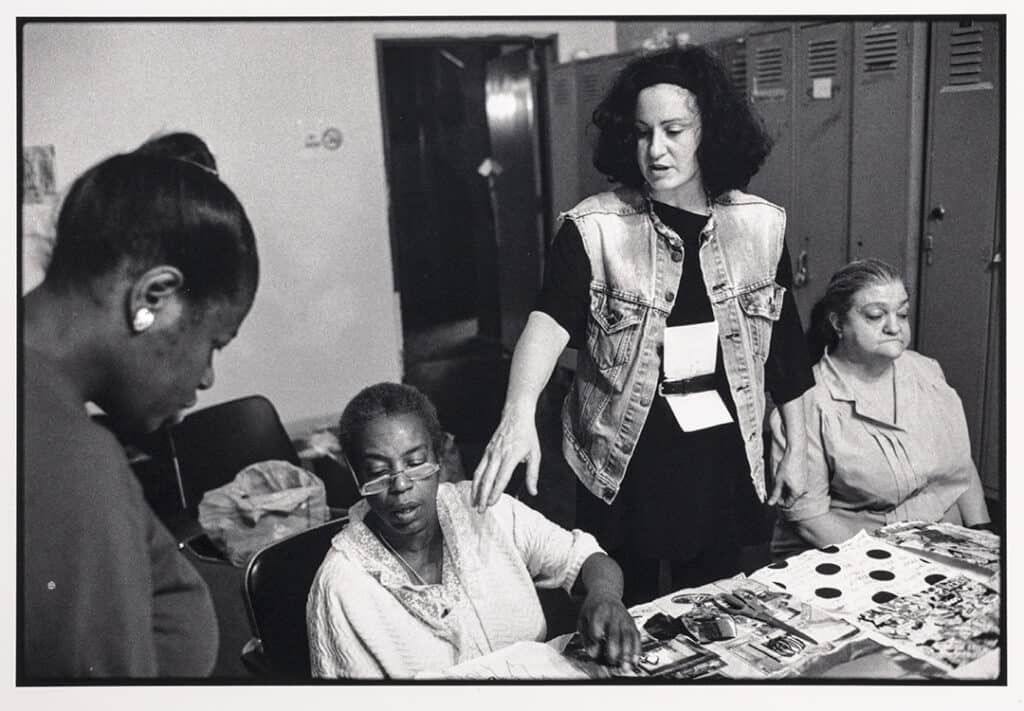

In 1990 Sandrow founded The Artist and Homeless Collaborative at the Park Avenue Armory Shelter for Homeless Women. “It was a profound experience to see the relevancy of art to life for those who had lost the place they thought they belonged which was their home.” Trust and privacy were paramount as many residents had husbands outside who wanted to kill them. Sandrow recounts, “I was there to listen and learn and as soon as the women experienced making art with me, and later my artist colleagues, they opened up. Art is an important medium for self-representation.” As a victim of abuse herself, Sandrow admits, “It gave me the courage to expose my own personal history and transformed the holding of secrets into works of art.” At the time of AIDS and when many artists were being blamed for cultural woes it was extremely gratifying for Sandrow and her colleagues, “As soon as we got off the elevator the women would greet us, ‘The artists are here!’” Powerful images from this experience were part of a recent exhibition “Art for Change: The Artist and Homeless Collaborative at the New York Historical Society.” (Images courtesy of NYHS).

The Hamptons have represented a retreat for Sandrow since first coming out with her husband in the ‘70s. They acquired his family’s carriage/gatehouse in Shinnecock Hills, dating to 1891 thought designed by Grosvenor Atterbury, and recently a carriage house on the adjacent property once belonging to William Merritt Chase thought designed by Stanford White. “As an artist this captured my imagination because years earlier, I’d titled my onsite project open air studio spacetime in homage to Chase,” said Sandrow. “This is my place to make art, reflect.”

Sandrow turned her activism close to home in this case, researching and taking up the cause of the Shinnecock Nation and looking at its rich and complex history, noting the discrimination and bad treatment of Shinnecock Nation members. A chance meeting with a rooster crossing the road led to raising chickens and Sandrow has shared five thousand eggs with Shinnecock food pantry since March 2020. It is the literal nourishment to the soul. She has been an active advocate for preserving ancestral lands since the turn of this century saying after the sacred burial ground at Sugar Loaf Hill was returned to the Tribe, procured by funds from the Community Preservation Fund, Peconic Land Trust and Roger Waters, “It was the first time I had seen smiles on some of my friends’ faces.”

Acknowledging the economic challenges faced in land preservation, Sandrow has a proposal, “Would Real Estate professionals, who’s expertise has raised property values, be willing to create a fund, say one percent of their annual profits, with those monies making up the difference between the appraised and market values of the land that the CPF could acquire? It would be their unique opportunity to give back while moving our community forward. Please let me know.”

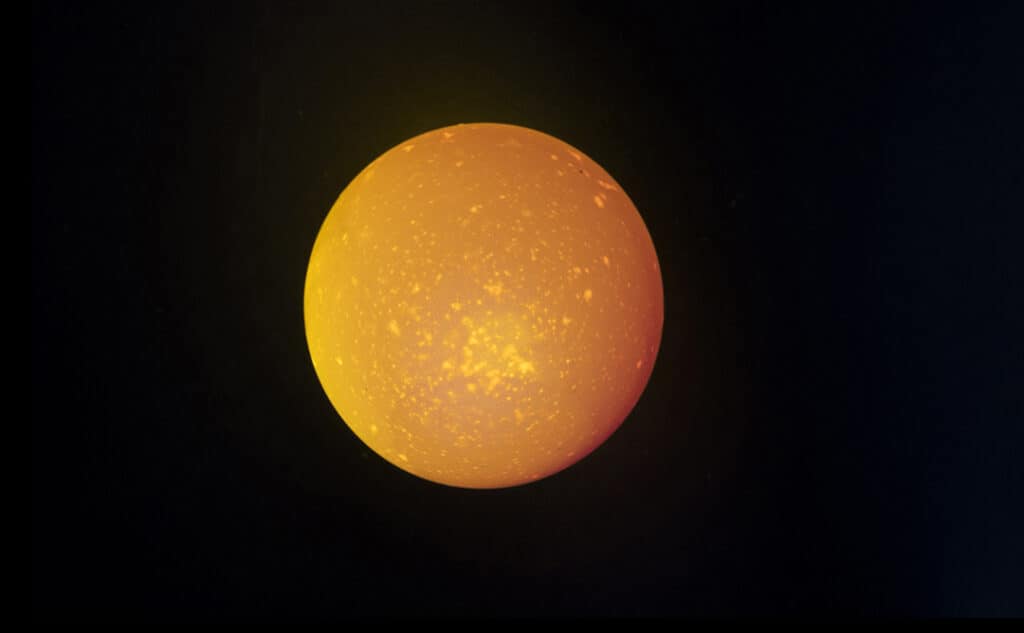

While aware of the many challenges still ahead, it is her “Portrait of a Chicken as an Egg Within a Golden Rectangle”, where Hope finds hope and indeed as Emily Dickinson wrote “it is the thing with feathers.” She says, “I discovered while photographing the eggs being candled they look like suns and moons and planets that have a similar cycle.” You could say in life and in art, it has come full circle.

![Join us May 6th at The Harmonie Club for the Spring Salon Luncheon, a beautiful gathering in support of a truly meaningful cause. Together, we’ll raise critical funds and awareness for @campgoodgriefeeh—@eastendhospice’s summer bereavement camp helping children and teens navigate loss with compassion, connection, and healing. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491527001_18506092897030135_3117653411609489602_nfull.webp)

![Welcome to this exquisite custom-built home in the prestigious Quogue South estate section, just moments from Dune Road and some of the world’s most breathtaking ocean beaches. Completed in 2024, this expansive shingle-style residence offers 6 beds, 7 full and 2 half baths, a separate legal guest cottage, heated gunite saltwater pool with spa, all set on a beautifully manicured 0.74± acre lot. Represented by @lauren.b.ehlers of @brownharrisstevens. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491516869_18505931593030135_4655757731678000577_nfull.webp)

![Discover 11 Oyster Shores, a unique marriage of thoughtful design, uncompromised execution and meticulous craftsmanship expressed across nearly 6,000± sq. ft. of highly curated living space. Brought to life under the watchful eye of Blake Watkins, the visionary behind WDD, the project is a refreshing departure from the ordinary. Represented by @nobleblack1 of @douglaselliman. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491440257_18505740808030135_9064730571228880657_nfull.webp)

![Reserve your ad space now in the Memorial Day “Summer Kick-Off” Issue of #HRES! 🍋 Be seen by high-end buyers and sellers across the Hamptons, Manhattan, and South Florida—just in time for the start of the season. Secure your spot today and make waves this summer 🌊☀️ [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491441694_18505573426030135_4475989184561040528_nfull.webp)

![Tuesday, April 15, was Tax Day for most, but for someone in Palm Beach, it was closing day! The nearly 8,00± sq. ft. Mediterranean-style residence at 240 N Ocean Boulevard, with direct ocean views and a private, 100-foot beach parcel, closed at exactly $26,670,750. The seller was represented by Jack Rooney of @douglaselliman and Elizabeth DeWoody of @compass while Dana Koch of @thecorcorangroup brought the buyer. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491445351_18505056166030135_4907944420436119099_nfull.webp)

![Previously featured on our 2024 Columbus Day issue cover, 74 Meeting House Road has officially sold! This stunning new construction in Westhampton Beach offers the perfect blend of thoughtful design and timeless style. Congratulations to @kimberlycammarata of @douglaselliman who held the listing! [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491441951_18504901357030135_2664904795600183799_nfull.webp)

![Located South of the highway in Southampton this 4 bedroom, 5.5 bath multi-story property, offers extensive exterior architectural detail throughout. 60 Middle Pond Road offers breathtaking views and tranquil living, nestled along the serene shores of Middle Pond and Shinnecock bay. Represented by @terrythompsonrealtor @douglaselliman. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/491451873_18504686110030135_5284427082339135969_nfull.webp)