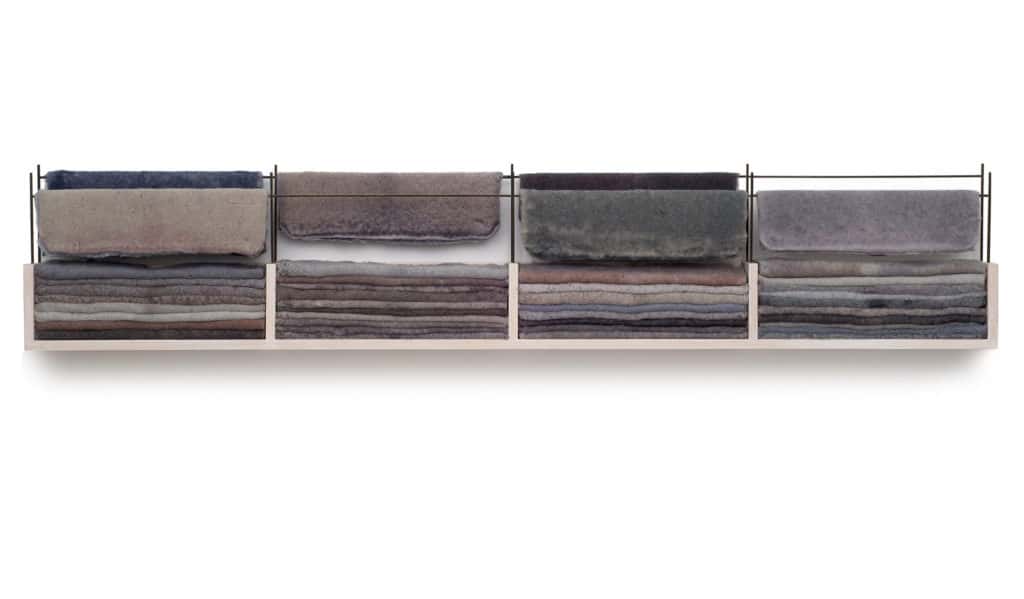

The next time you clean out the lint tray in your spin dryer, resist the impulse to wad the lint into a ball and throw it away. Instead, keeping the lint intact, lay it on a flat surface. Repeat this process for about a year until the oblongs come to resemble counterpanes in an eighteenth century orphanage or horse blankets. Now carefully fold them as if they were really were counterpanes or horse blankets. Admire your work and marvel at the striations of color — all the greys and mauves and bluish hues. Think about how many of the acts we perform thoughtlessly, day after day, and to which we ascribe little value, are in themselves art and so too — in the right hands — are the detritus of our works and day, and then you’ll begin to understand the art of Carolyn Conrad. “When I pulled the material from the trap, the fibers looked so beautiful to me,” says Conrad from her studio. “The material was so fragile and delicate, well, I thought it deserved our attention.”

The dryer lint assemblages fit into the larger framework of Conrad’s decades-long inquiry into domestic spaces and the nature of home. Ongoing work in that vein includes her moody images of what appear to be true-to-scale houses in fields. In fact, Conrad constructed, arranged, and photographed every element in the picture, from the 5 x 8 houses that she makes out of clay and laminated balsa or bass wood to the heavy canvas fabric that she dyes and re-dyes in shades of storm-light-grey to approximate the sky. Once assembled on a table in her studio, she photographs the scene and prints it on archival paper.

The wooden house series evolved organically, in the shadow of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. “I felt I needed to make more contact with family,” Conrad recalls, “in a personal way.” And so, tentatively — she wasn’t a skilled photographer at the time — she began to photograph the clay figures, busts, and ordinary objects in her studio. “At first I was just playing around,” she says. “But once I got going, I thought, ‘Goodness, maybe I can do something serious with this.’”

That “something serious” speaks of our vanishing rural landscapes, atomized societies, and increasingly hermetic notions of home. It’s no coincidence that Conrad, who did graduate work in fine arts at New York University, held a day job for over a decade in the communications department of an international architecture firm. Hence, dealing with elevation plans and “very pared down structural forms” are second nature to her.

For all the simplicity of her work, its gestation, Conrad says, is long. “I get excited about a concept or a process, but when I try to execute it, I’m usually disappointed. So the initial failure forces me to go in an unexpected direction. My pieces have a formal quality, they do, but there’s a lot of accident along the way.”

![Homeowners are faced with the daunting task of choosing the right kitchen design — one that will remain timeless for both entertaining and day-to-day functionality. With a focus on luxury, clients are increasingly leaning towards clean, modern aesthetics but are hesitant to embrace a fully contemporary look. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/467244043_1082221510295882_2208387561574057218_nfull.webp)

![Experience the epitome of coastal country living in this newly constructed, quality craftsmanship waterfront home on James Creek, leading to Peconic Bay. With 80± ft. of prime waterfront, 4060 Ole Jule Lane showcases thoughtfully landscaped grounds, a bluestone patio, outdoor shower, and a refreshing saltwater pool. Represented by @nataliealewis of @coldwellbanker. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/467188671_18474458155030135_7164624532118372206_nfull.webp)

![Welcome to 122 Mill Pond Lane, an impeccably conceived and meticulously maintained residence in a dramatic west-facing setting on Mill Pond. Throughout the home are thoughtfully considered elements that reinforce the home’s clean, modern sensibility. Represented by @kraelyllahamptons of @hamptonsrealestate. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/466787127_18474263443030135_2753720635361764689_nfull.webp)

![Perched atop the dunes at Louse Point sits 2 picturesque homes at 88 & 86 Louse Point Road, both perfect for enjoying all seasons that East Hampton has to offer. Each thoughtfully designed home maximizes the topography to allow seamless indoor/outdoor living and entertaining. Represented by @petrieteam of @compass. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/466619407_18473886082030135_7330054085188815713_nfull.jpg)

![Get cozy every Friday at Canoe Place Inn! 🍫🔥 Gather around the fire on our Garden Lawn for Fireside Fridays all season long, where evenings are warmed up with hot cider, hot chocolate, s’mores, and cocktails. Enjoy live acoustic music on select dates, and with your first drink, receive a complimentary s'mores kit! [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/466374901_1761070534297706_6837753985329213061_nfull.jpg)

![Musical Superstar and Sag Harbor resident Billy Joel has listed his 26± acre Long Island estate for $50M. Assembled over time on adjoining parcels, the Centre Island compound features a 20,000± sq. ft. main home plus several additional structures—all with access to 2,000± ft. of private shoreline boasting a dock and a boat ramp. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/465973748_18473309701030135_6935355293028123088_nfull.jpg)

![51 Mashomuck Drive presents an exquisite estate spanning 1.1± acres with 145± ft. of bulk-headed waterfront. The main residence, offering captivating vistas of Sag Harbor Bay and Shelter Island, encompasses 7,800± sq. ft. of living space, boasting 7 beds, 9.5 baths, and a media room/gym area. This turn-key retreat embodies opulence and comfort, inviting a life of unparalleled luxury. Represented by @cindyascholtz and @jvonhagn of @compass. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/466104990_18473128246030135_2802294086252776198_nfull.jpg)