Artist Dr. Leslee Stradford Breathes Life Into Loss

What does it mean to pick up the baton from your ancestors, even if it is charred?

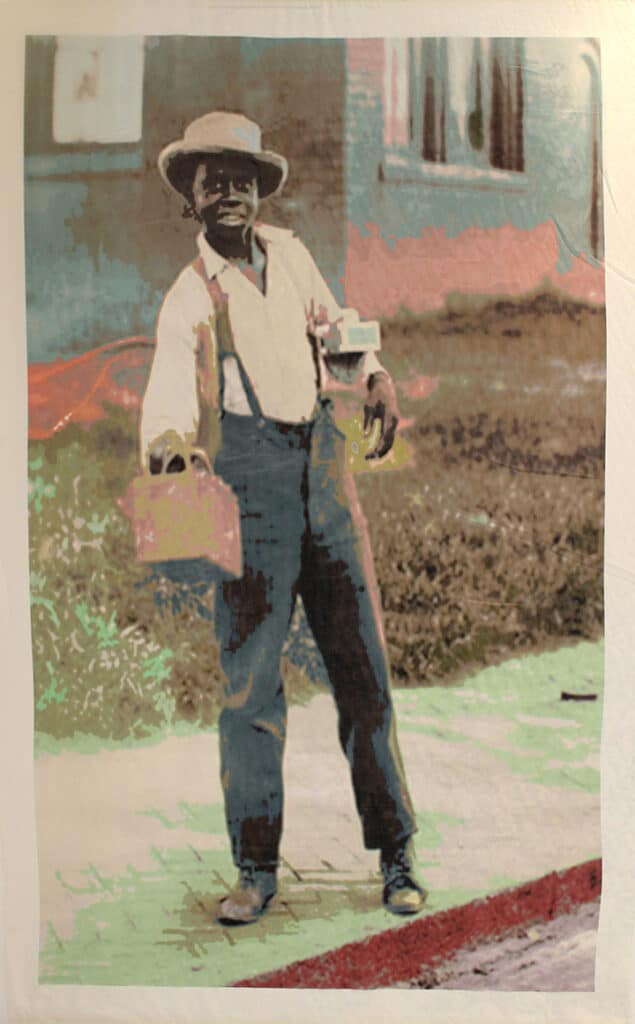

Artist Dr. Leslee Stradford reaches back to her family roots to create “The Night Tulsa Died: The Black Wall Street Massacre 1921,” both a book and an exhibit at the Julie Keyes Gallery in Sag Harbor. “Once when I was six Grandma Mumzie told me the story of ‘The Night Tulsa Died.’ She told me other scary stories too,” says Stradford, “But this one was real.”

On May 31st 1921 a prosperous black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma experienced the single worst incidence of racial violence in American history. In the course of 16 hours the 37 blocks of a thriving black community in Greenwood were burned to the ground with estimates of 300 to 3,000 or more killed including women and children. Stradford’s great grandparents were there and barely escaped the carnage which was only whispered about for decades.

With the oil boom in Oklahoma a group of blacks, some soldiers back from World War I, formed an enclave of professional men and women of color, with well-educated children. Stradford’s great grandfather owned one of the premiere hotels in the US in the Greenwood District which included movie theaters, shops, businesses, a hospital, schools and two newspapers. The money was kept in the community, reportedly passed between its members 37 times before leaving. “My great grandfather had been in Tulsa and had a wonderful hotel. He was an attorney and had friends who were bankers and doctors and they had everything in the black Tulsa neighborhood that they had in the white neighborhood but everything was segregated,” recounts Stradford.

When a black shoeshine boy tripped in an elevator on the way to the restroom and bumped into a young white woman elevator operator onlookers called the police. A mob of over 2,000 white men deputized by the police systematically shot the residents, looted their homes, then burned them to the ground. Only 1,000 of an 11,000 population stayed in the tent city with Stradford’s great grandfather able to escape aided by his son. His son and her aunt were able to clear his name in 1997 after being called as a community leader, an inciter of the “riot.”

Stradford says, “There were so many bodies that it clogged the Arkansas river. The stories are horrific. Some never saw their relatives again.”

On the 100th anniversary Stradford wanted to honor this trauma passed on through her DNA and create a series of silk screens inspired by the events. “I was on sabbatical in Beijing and I was working with silk as textiles. I thought that would be a good material because it was fragile – kind of like the story — and that it would be easily transportable,” says Stradford, “I was compelled to do it. The project chose me. I tell the story in my own abstract expression. It’s about color and imagery and emotion.”

Stradford creates images on the computer using historical photographs including her family’s and manipulates and colorizes them, in some cases gilding them. These are then printed on the silks. The power of Stradford’s work suggests not only history but the story of black/white relations at large. While viewers may see tragedy there is also a sense of souls transcending the earth plane to make sure their stories are not forgotten even if there was never any justice.

“What has to happen for our society is for everyone to really understand the other person,” says Stradford, “That’s why I like to travel because you get to see how people live in other circumstances. It takes being in another environment and maybe one that’s not so comfortable to see how other people really are.” For those looking back over 100 years, her work is a portal to the past and a path to the future.

!['The Maples' is a prestigious generational compound of two extraordinary estates: 18 Maple and 22 Maple. This rare offering, designed by luxury architect Lissoni partners New York and developed by visionaries Alessandro Zampedri-CFF Real Estate and JK Living, redefines opulence with the highest quality of craftsmanship and captivating views of the Atlantic Ocean. Represented by @nycsilversurfer and @challahbackgirl of @douglaselliman. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/438891010_1083749139481747_7890082604579275354_nfull.jpg)

![Featuring 360-degree water views on Mecox Bay, the Atlantic Ocean and Channel Pond, 1025 Flying Point offers the ultimate beach cottage that is flooded with natural light. With panoramic views, proximity to the ocean, and a private walkway to Mecox bay for kayaking or paddle boarding, this truly is a special retreat. Represented by @ritcheyhowe.realestate and @hollyhodderhamptons of @sothebysrealty. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/438994305_737511778456166_4602476013493875279_nfull.jpg)

![Attention advertisers! 📣 Secure your spot in the highly anticipated Memorial Day edition #HRES. Reach thousands of potential clients and showcase your brand in one of the most sought-after publications in the Hamptons, NYC, Palm Beach, and beyond. Contact us now to reserve your ad space! [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/438549843_275102939023235_6718257301437562124_nfull.jpg)

![You eat with your eyes, and on the East End, it’s important that what you eat looks just as good as how it tastes. At @rosies.amagansett, the restaurant itself is plenty photo-worthy with blue ceramic tiling and yellow and white striped fabric wallpaper. But for a dish that will light up your photos, head directly to the salmon tartare! [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/437094269_7296727147115953_1594410326824303644_nfull.jpg)

![We were honored to be the media sponsor for @blackmountaincapital's open house event with @jameskpeyton and @jfrangeskos at 11 Dering Lane in East Hampton! Other sponsors included @landrover, Feline Vodka, @rustikcakestudio, @la_parmigiana, @lahaciendamexicangrill11968, @homesteadwindows, Stone Castle, @talobuilders, and @thecorcorangroup.

A big thank you Carrie Brudner of Black Mountain Capital for putting together this fabulous event! [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/437081213_762912965932136_6847332836522786568_nfull.jpg)

![Blooms Galore at the Long Island Tulip Festival! 🌷✨ Mark your calendars for April 15th as the vibrant tulips at @waterdrinkerlongisland burst into full bloom! Enjoy a day filled with colorful splendor, food trucks, live music, and more. [link in bio]](https://hamptonsrealestateshowcase.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/437083429_974242677583725_6855805712693638343_nfull.jpg)